In early February 1776, Scottish advocate James Boswell listened as fellow lawyers argued a case concerning day laborer wages before the Court of Session. Scotland’s supreme civil court resided then as it does now in Parliament House, part of the Parliament Square complex in Edinburgh, just a short walk down from the Castle along what is today known as the Royal Mile. The court sat in the space once occupied by the Parliament of Scotland before the 1707 Treaty of Union eliminated the kingdom’s legislature and created a combined Parliament in Westminster, England.

Boswell, who was not involved in the litigation at hand, watched advocates James Dickson, Alexander Wight, David Armstrong, and John Maclaurin deliver oral arguments in the court’s Inner House, where the full court heard cases on appeal. Boswell thought the case “was well argued on both sides,” but as he knew, the judges would give greater weight to the printed documents that litigants and their counsel submitted to the court rather than to the advocates’ oral performances. “Ours is a court of papers,” Boswell later wrote in his journal. “We are never seriously engaged but when we write. We may be compared to the Highlanders in 1745. Our pleading is like their firing their musketry, which did little execution. We do not fall heartily to work till we take to our pens, as they to their broadswords.”

Boswell’s observation on the day’s legal proceedings reflected the centrality of Session Papers, the documents offered in this digital archive, to the Scottish legal system and its highest civil court. Session Papers are the privately printed documents filed with the court as part of the litigation process, most often in appellant cases like the one Boswell witnessed that February morning.

In 1710, the Court issued an Act of Sederunt (the rules by which the Court governed itself and legal practice before it) obligating lawyers to present legal documents in printed form. The court sought to reduce the errors associated with copying manuscripts by hand. That order led to the creation of legal documents unique to this period. English and American courts largely did their business in manuscript. The Court of Session did much of its work in print.

Session Papers were never really intended for public consumption. On occasion a litigant published a document to damage his opponent’s public reputation, but in general Session Papers remained in the purview of the lawyers and professional legal organizations who wrote, read, collected, and curated them.

An estimated quarter million documents dating to the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries currently reside in British and American libraries.

The Scottish Court of Session Digital Archive Project (SCOS) is part of a larger international collaboration between the University of Virginia School of Law Library and a consortium led by the Centre for Research Collections at the University of Edinburgh. Partners include the Library of Congress, the Faculty of Advocates Library, and the Writers to the Signet Society Library. Their collective goal is to create a comprehensive digital archive using International Image Interoperability Framework (IIIF) technology to provide researchers with access to Session Papers held by many different institutions.

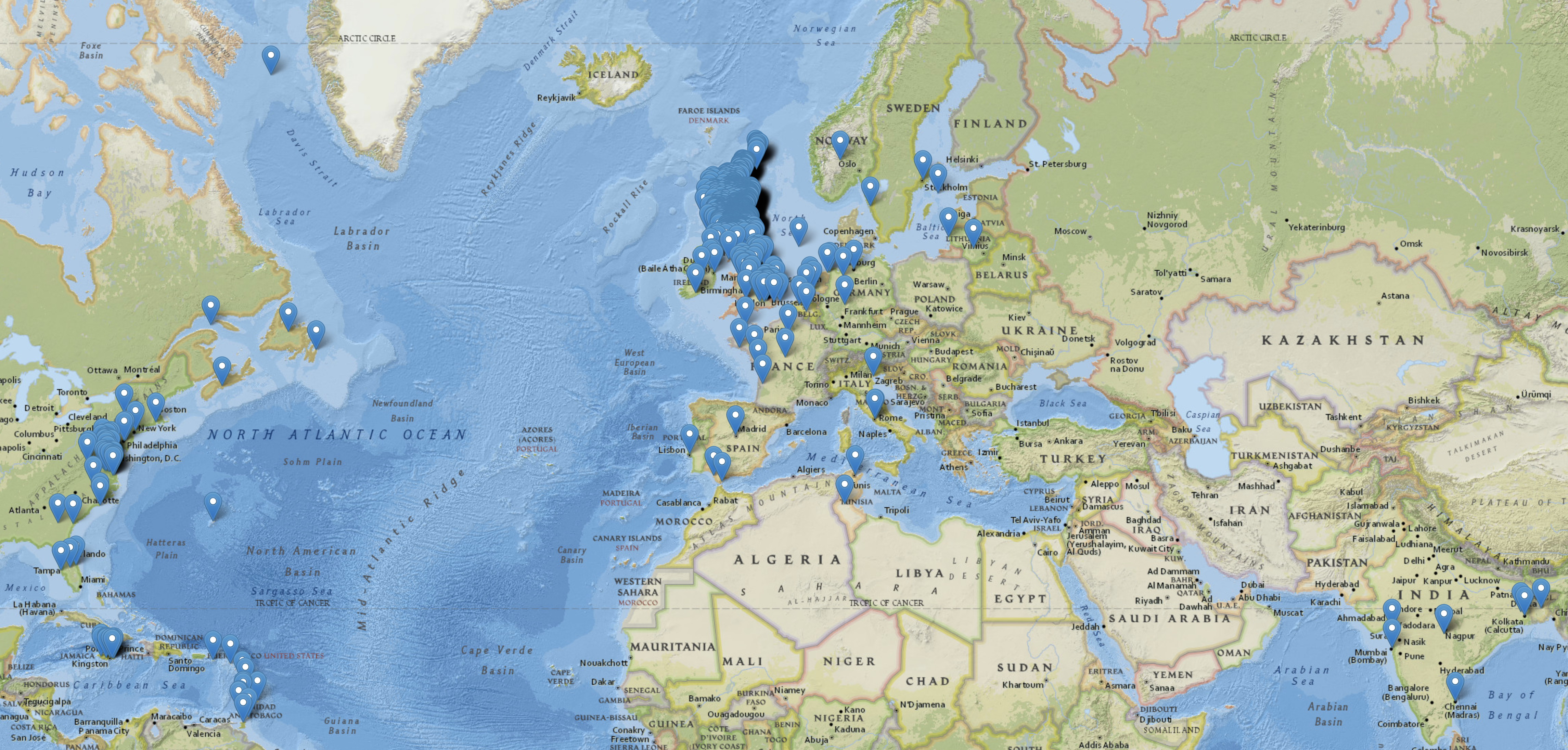

SCOS is one element of this wider transatlantic initiative. Once complete, SCOS will feature litigation dating between 1757 and 1849 held by the UVA Law Library and the Library of Congress. Fully cataloged, indexed, and richly described with biographical and spatial metadata, the Session Papers in SCOS will enable researchers to ask new and important questions about the past.

SCOS makes a specific intellectual contribution to the collaborative effort by framing Session Papers as remarkable windows into the everyday lives of the ordinary and powerful in Scotland and the British Atlantic world in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. As a civil tribunal, the Court of Session heard cases involving marriage, divorce, inheritance, transatlantic commerce, slavery, elections, landed estates, intellectual property rights, religious communities, war, and rebellion. And while it had jurisdiction over Scotland only, Scots’ entanglement with the wider world meant that by necessity North Americans, Africans, Europeans, other peoples pursued their legal interests before the court. The Session Papers produced during the litigation process offer us a compelling way to explore how individuals in Great Britain, North America, Africa, Europe, and the Caribbean navigated an era of great upheaval and historical change.

This essay offers a very basic introduction to the Court of Session and Session Papers. It is by no means comprehensive and it presumes that SCOS users have little familiarity with the Court or Session Papers. This is by design. Session Papers are a means to explore the lives of people as they circulated throughout the British Atlantic world in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Having a sense of the court’s history, its inner workings, and the creation and curation of Session Papers will help readers uncover the hidden histories within them.

The essay offers:

- A brief historical perspective on the Court of Session

- An overview of court procedure and the creation of Session Papers

- The curation of Session Papers in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries

The companion video tutorials (coming soon) will help you navigate the digital archive. We also encourage you to visit the Scholarship and Project Team pages for the latest SCOS updates and contributors.

Readers wishing to know more about the topics discussed in the essay below are encouraged to consult the reading list provide at the end.

History

The Court of Session was founded in the early sixteenth century. In 1532, the Scottish Parliament passed the College of Justice Act, creating the Court of Session. King James V’s government modeled the new tribunal after the Parlement of Paris, one of the provincial appellant courts in pre-revolutionary France. The original College of Justice consisted of fourteen members, called “Senators” or “Lords of Session,” who were equally divided between laymen and members of the clergy. Two additional men, the Lord President and the Lord Chancellor of Scotland, presided over the court.

An early twentieth-century stain glass window in Parliament House depicts a representation of the court's first meeting. James V, seated on a golden throne, convenes the first Session while Lord Chancellor Gavin Dunbar, Archbishop of Glasgow, and the other Lords of Session look on. In 1640, Parliament reformed the court by excluding clergymen from the senators’ ranks. Thirty-two years later, in 1672, Parliament created the High Court of Justiciary, Scotland’s supreme criminal court, by designating five Lords of Session to sit with a Lord Justice General and a Lord Justice Clerk to hear criminal cases.

The 1707 Treaty of Union uniting the parliaments of England and Scotland (the crowns had been united one hundred years earlier) preserved each kingdom’s respective legal systems. Scots Law, with its foundations in Roman Civil Law, would remain separate from common law England, although Sessions Papers and law reports make clear common law’s growing influence in Scotland in the years following the union. Article XIX of the treaty granted Scotland’s civil and criminal courts “the same Authority and Privileges as before the Union, subject nevertheless to such Regulations for the better Administration of Justice, as shall be made by the Parliament of Great Britain.” The House of Lords served as the final court of appeal for Great Britain until the creation of the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom in the early twenty-first century.

By James Boswell’s era, Acts of Sederunt had greatly expanded membership in the College of Justice. In the mid-eighteenth century, the College consisted of the judges of the two supreme courts, the Faculty of Advocates (the professional body of lawyers whose members were the equivalent of English barristers), the Society of the Writers to the Signet (solicitors who drew up legal documents and affixed the monarch’s signet, or seal, to give them legal authority), and a host of other officials such as the Clerks of Session and the Keeper of the Advocates Library. The College of Justice's collective goal was “delivery of justice to the king’s subjects.”

The members of the College of Justice formed a community that was in some ways separate, yet tightly woven into the intellectual and social fabric of Edinburgh during the Scottish Enlightenment. Boswell’s Edinburgh Journals offer a remarkable portrait of the College’s social and creative intimacy. Boswell was a close associate of judge James Burnett, Lord Monboddo, and advocates such as Robert MacQueen and John Maclaurin. Both men later became judges on the court. He was also a critic of the Dundas family, including Lord President Robert Dundas of Arniston and his younger half-brother, Henry Dundas, a politically ambitious fellow advocate. In 1775, George III named the 33-year old Dundas as Scotland’s Lord Advocate, the monarch’s chief legal representative in the kingdom. Perhaps most importantly for Boswell his father, Alexander, Lord Auchinleck, sat on both the Court of Session and the Court of Justiciary.

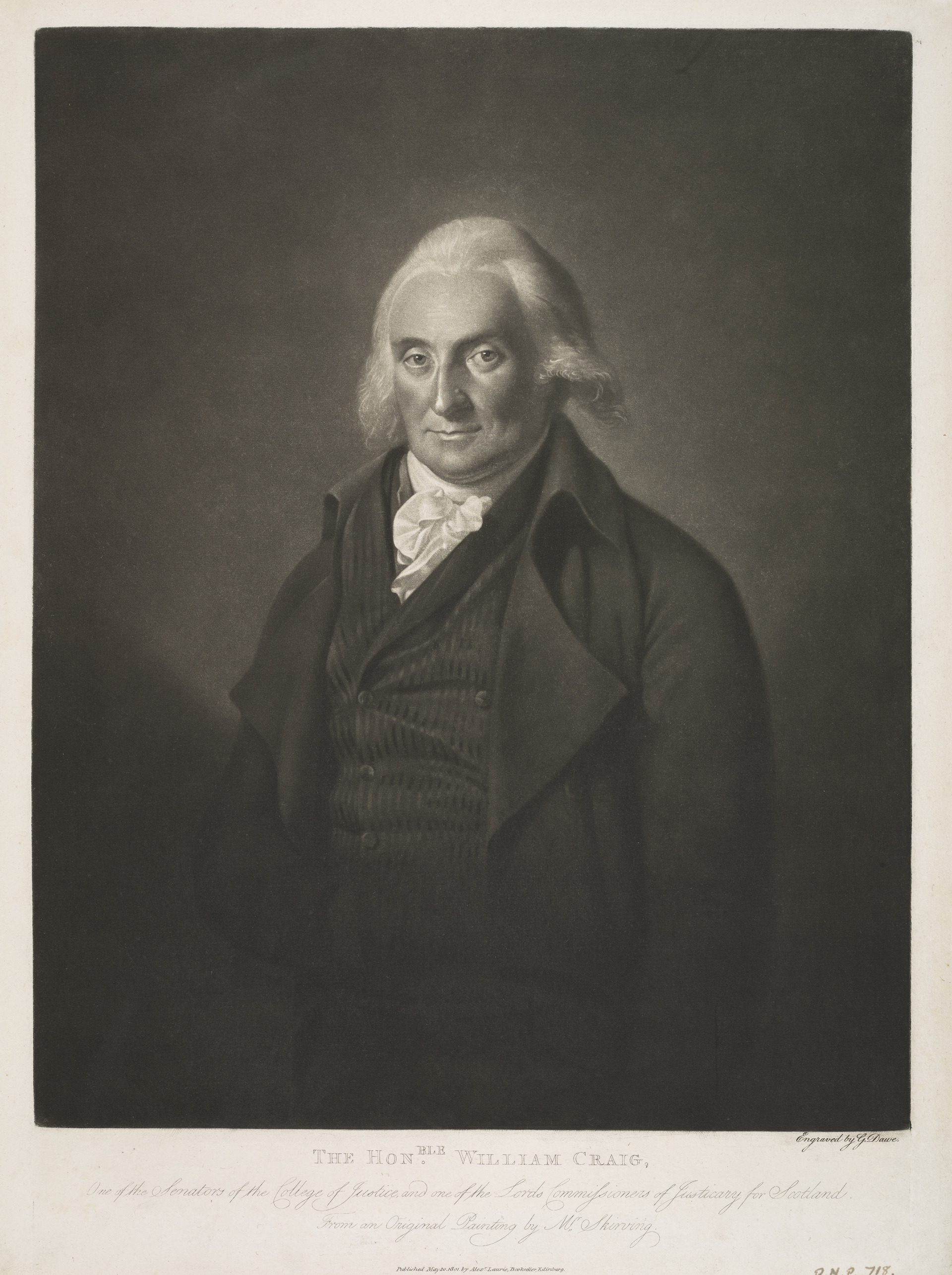

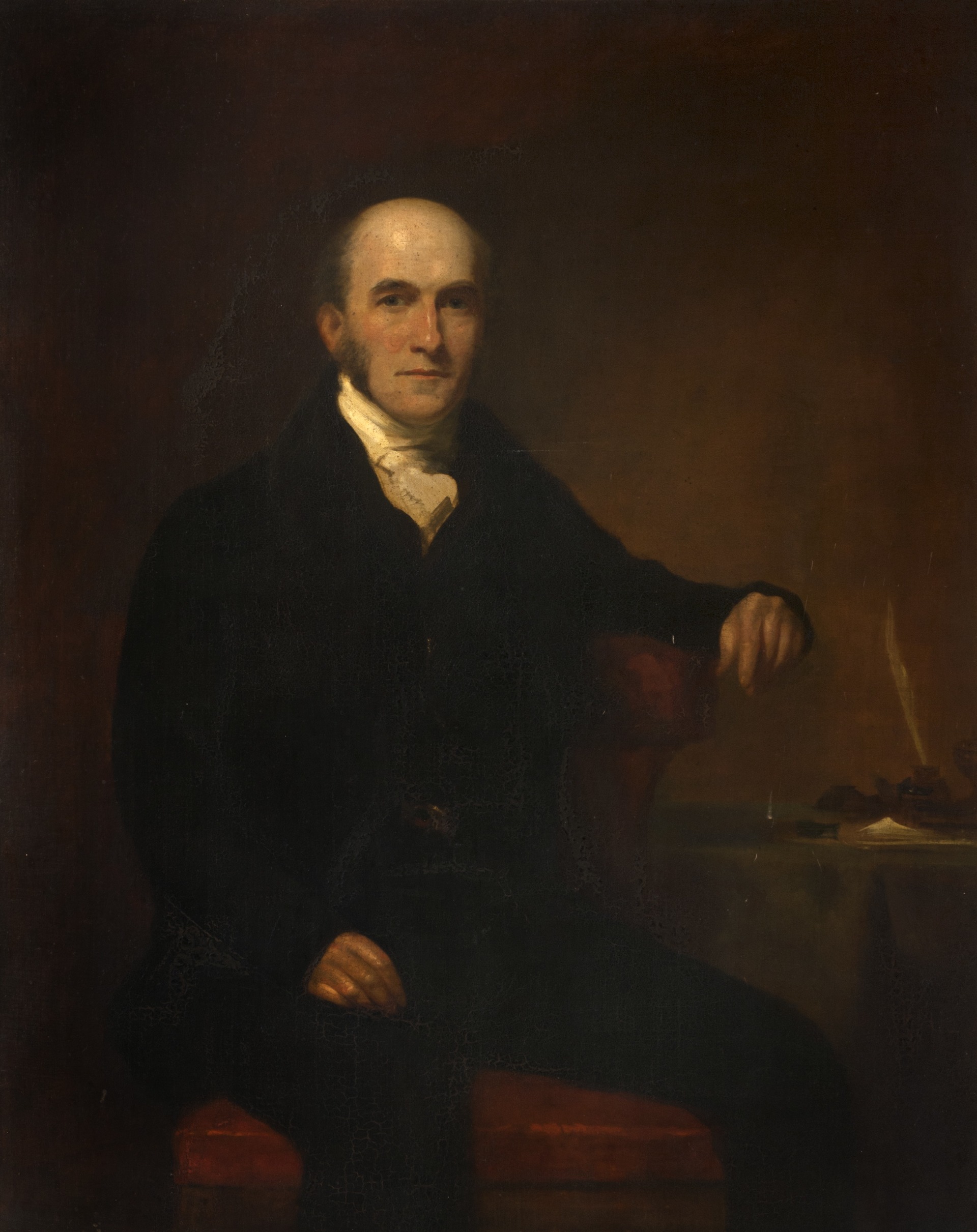

Boswell, who became a prominent author in his own right, considered Henry Home, Lord Kames an important mentor. Raised to the bench in 1752, Lord Kames authored numerous philosophical works, including Sketches of the History of Man (1774), one of the most important works on stadial theory. William Craig, the advocate who began the Session Papers collection featured in this digital archive, was a close friend of fellow lawyer Henry Mackenzie, author of the sentimental novel The Man of Feeling (1771). Craig later became a judge on the Court of Session with the judicial title “Lord Craig.” He contributed several essays to Mackenzie’s periodicals, The Mirror and The Lounger. Sir Walter Scott, whose father was a Writer to the Signet, became an advocate in 1792. These men practiced and shaped Scots law in Edinburgh as the Enlightenment in turn shaped them.

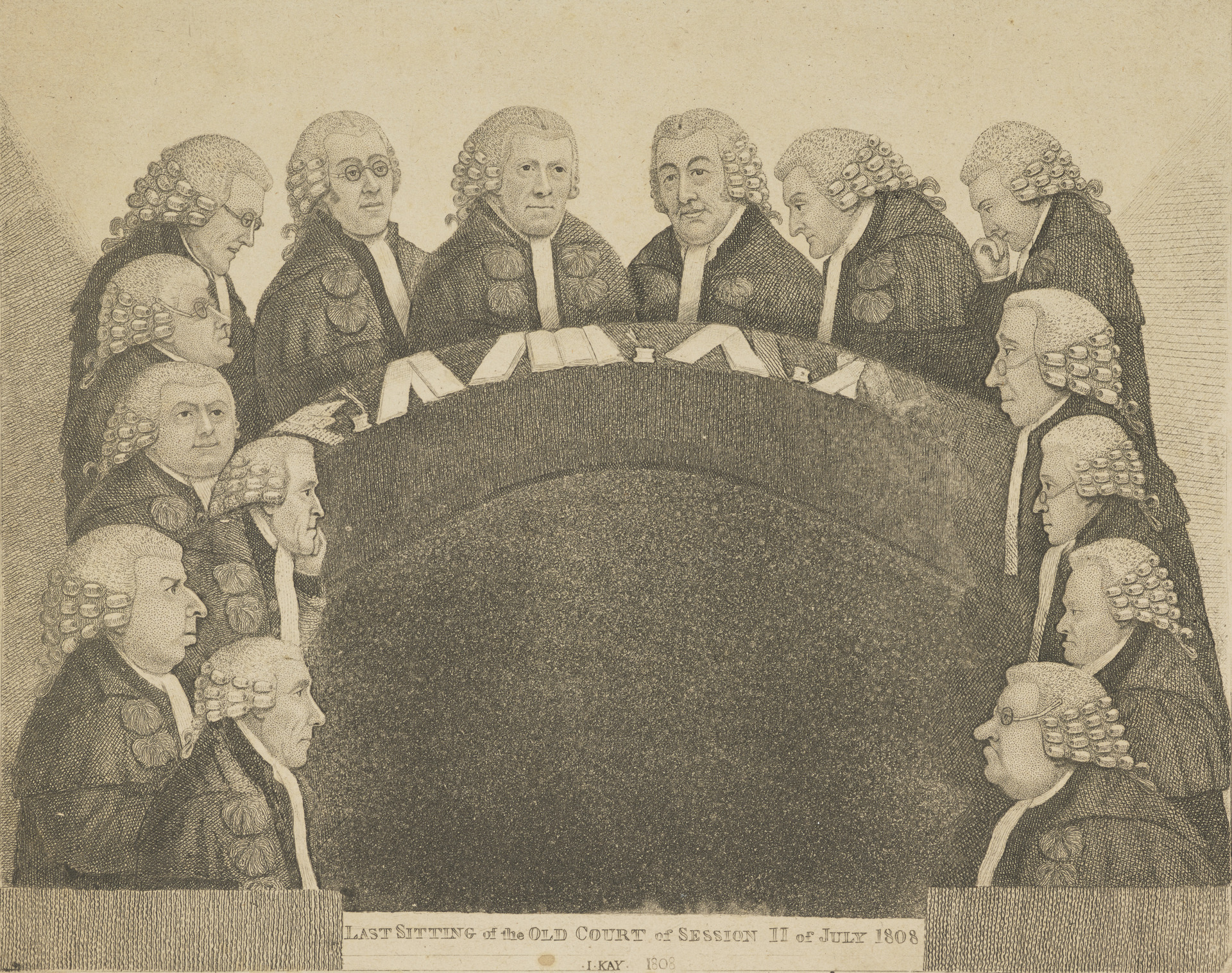

The British Parliament began reforming the Court of Session in the early nineteenth century. The government sought to improve the court’s efficiency, codify existing practices, and introduce jury trials. In 1808, Parliament split the court into a First Division and Second Division. The two divisions possessed co-equal authority, with the reform intended to alleviate a growing case backlog. Subsequent acts formalized the existence of the court’s Outer House and the Inner House (key institutions that are discussed below) and established jury trials in civil cases.

But how did cases come before the court and how did litigation proceed once a party filed suit?

In the next section, we will examine the creation of Session Papers through an exploration of court procedure. Knowing how litigation moved through the court system helps us to understand what Session Papers can reveal about the past. Specific document types tell us much about where a cause (case) stood at any given moment during the litigation process, what information they contained, and the court’s or a litigant’s strategy to resolve a legal dispute. Tracing the life of case before the court will help readers use the documents in this digital archive more effectively.

Procedure

The Court of Session served as both a court of first instance and as an appellant body. A litigant could initiate a cause in the court or they could file an appeal asking the Lords of Session to overturn a lower Scottish court’s ruling. It had final jurisdiction over civil matters. Only the House of Lords could reverse the court’s decisions.

The court dealt with two types of causes. An “ordinary process” included most litigation brought before it. Individual judges handled these cases and issued rulings. Litigants might then ask for a full court review. In an “extraordinary process,” which included cases dealing with heritable bonds or bankrupt estates, an individual judge did not issue a ruling. Instead, he prepared the case for a decision by the full court.

In the mid-eighteenth century the Court of Session consisted of the Outer House and the Inner House. For our purposes it is enough to know that a process began in the Outer House in one of two ways. A litigant might initiate legal action directly in the Outer House, or they petitioned to transfer it from a lower Scottish court.

Advocates worked in collaboration with law agents to prepare a case for a hearing. Agents were solicitors who were qualified to act in causes before the court, a group that included the Writers to the Signet. Generally, agents were a client’s first point of contact. They in turn brought a case to an advocate. Together, advocates and agents began legal proceedings on their client’s behalf.

Initiating a process in the Outer House began when a Writer to the Signet issued a summons in the king’s name. The king’s seal gave the document legal authority. It detailed the Pursuer’s (plaintiff’s) libel, or complaint, and asked for a Decreet, or order, in the pursuer’s favor. The summons also contained a warrant commanding the Defender (defendant) to answer the charges. Assuming that the defender responded with defenses against the pursuer’s claims, the case was then enrolled, or recorded, in one of two enrollment books and a hearing was then scheduled before the Lord Ordinary in the court’s Outer House.

The Lords of Session took turns each week sitting in the Outer House as Lord Ordinary of the Week. Only the Lord President was excused from this duty. Advocates like Craig or MacLaurin delivered oral arguments before the Lord Ordinary on behalf of a pursuer or defender. The Lord Ordinary, who had read the manuscript libel and defences, would then issue an Interlocutor, or judgement, in the case. His decision could be appealed, but it became final with the court’s full authority if either of the litigants failed to act within a specified timeframe.

The Lord Ordinary could also order the parties to submit written briefs known as Memorials or Condescendences if particular points of law or fact remained unclear or confusing. Legal counsel submitted these briefs before the Lord Ordinary delivered his interlocutor. They might be printed later if the case moved forward to the Inner House.

A pursuer or defender who disagreed with the Lord Ordinary’s ruling could ask him to alter his interlocutor via a Representation. He could refuse the representation or order the opposing party to answer the new complaint. Irrespective of those two options, the Lord Ordinary was obliged to issue a new interlocutor that reaffirmed his original decision or pronounced a new one.

Cases might also arrive in the Outer House through a Bill of Advocation or a Bill of Suspension. The Lord Ordinary for Bills handled these matters, although the Lord Ordinary of the Week often fulfilled both rolls. A Bill of Advocation was an application to remove a legal proceeding from an inferior court directly to the Court of Session. A Bill of Suspension asked the court to set aside, or suspend, an alleged improper action by a lower court. Either bill triggered an ordinary process in the Outer House.

What was it like to plead a case in the Outer House? We can get a sense of the court’s daily hustle and bustle through the artist Charles Martin Hardie’s late nineteenth century depiction of the Outer House as it might have appeared in Sir Walter Scott’s era. In Hardie’s work, Parliament Hall, with its magnificent hammerbeam roof made of oak drawn from the forests of Fife, frames our view. Our backs are to the south wall as we look north down the room’s long axis. If the northern wall had a window we might catch a glimpse of St. Giles’ Cathedral, the medieval church, just across the street.

Hardie may have drawn inspiration for his depiction of the Outer House from the author Thomas Carlyle. Carlyle, who championed the Great Man Theory of history, visited the court in November 1809. He is the young man who only just enters our frame of view at the far right. In his later years, Carlyle recalled:

“An immense Hall, dimly lighted from the top of the walls, and perhaps with candles burning in it here and there; all in strange chiaroscuro, and filled with what I thought (exaggeratively) a thousand or two of human creatures; all astir in a boundless buzz of talk, and simmering about in every direction, some solitary, some in groups. By degrees I noticed that some were in wig and black gown, some not, but in common clothes, all well-dressed; that here and there on the sides of the Hall, were little thrones with enclosures, and steps leading up; and red-velvet figures sitting in said thrones, and the black-gowned eagerly speaking to them,--Advocates pleading to Judges, as I easily understood. How they could be heard in such a grinding din was somewhat a mystery.”

Thomas Carlyle, Reminiscences ed. Charles Eliot Norton (London and New York: MacMillian and Co., 1887), 2:223.

The gaggle of advocates in the foreground commands our immediate attention. Sir Walter Scott, wearing his professional robes but not his wig, is surrounded by fellow advocates. Scott’s gesticulation and the lawyers’ body language suggests that he is speaking. Perhaps he is discussing legal strategy with fellow counsel or they are debating a finer point of law. They lean closer to Scott less out of a concern for client confidentiality than it is on account of the room’s noise level. As Carlyle suggests and as Hardie shows us, the Outer House is not a picture of judicial solemnity; it is a boisterous, crowded place in which hearings before the Lord Ordinary take place in the open amidst a clamor. Men mill about in conversation as they go about their business.

We can see the Lord Ordinary perched upon his “throne” in an alcove along the building’s eastern wall. This is Charles Hay, Lord Newton. An advocate pleads at the bar before him while what may be the opposing counsel lingers near. The pleading advocate uses his hand to direct his voice toward Lord Newton while the judge cups his ear in a struggle to hear the advocate’s words.

High above the Lord Ordinary, a man leans through a square window. He is the Macer, the court official responsible for calling parties to a hearing. The Macer is shouting the names of a purser and defender out into Parliament Hall, directing them to proceed to a particular judge or area of the court, which further complicates the Lord Ordinary’s ability to hear the advocate standing only a few feet in front of him.

Hardie has Lord Newton use his right hand to control the sound so that we may conveniently see his face and to suggest that the judge must also block noise coming from the northern end of Parliament Hall. A partition wall partially obstructs our view of what lies beyond, but through an entry way we catch a glimpse of people engaged in some kind of activity, including a man reading a paper. A café occupied the space behind the wall. So, too, did printers who churned out Session Papers for their advocate clients. The partition probably forced the sound of clinking dishes, printing presses, and conversation upward over the wall, thus compounding the Lord Ordinary’s and the advocate’s efforts to make sense of one another.

But the painting also obscures much about the people involved in the legal process. The work is in keeping with Carlyle’s Great Man theory, the nineteenth century idea that history is shaped by actions of powerful men. Hardie shows us the legal profession at work, one dominated by a white male patriarchal society. Neither women or people of color could serve as advocates or judges in this period. Perhaps they are laboring behind the partition wall, but we cannot see them. Nor can we see the clients whom these advocates represent.

Yet, as this digital archive demonstrates, women as well as free and enslaved people of color were ever present in the Court of Session, even if we cannot see them in Hardie’s work. Some of the advocates in the painting are no doubt representing women, and possibly former slaves, while an unseen Lord Ordinary on Oaths and Witnesses, who heard witness testimony, is hearing depositions from women in another case. Session Papers can help us to restore presences absent from Hardie’s painting.

The vast majority of cases never made it beyond the Outer House. One study has shown that between 1794 and 1807 the Outer House issued rulings in 89% of the 23,089 cases decided by the court.

The full court, which sat in the Inner House with a quorum of at least nine judges, ruled on the remaining eleven percent. These cases included ordinary processes on appeal or extraordinary processes presented directly to the Inner House.

A case reached the Inner House from the Outer House in one of two basic ways. On the one hand, litigants who remained unhappy with the Lord Ordinary’s interlocutor could file a printed Petition asking the full court to hear the case. The Lords of Session had the power to accept or refuse the petition without comment. On the other hand, the Lord Ordinary himself could refer, or report, an especially difficult case to the Inner House.

Inner House litigation produced the vast majority of surviving Session Papers. To see why, let us suppose that the Lord Ordinary decided to refer a case to the full court. He then ordered the litigants to produce Informations that stated their respective legal arguments and offered evidence to support their claims.

If the Lord Ordinary found certain facts or arguments were in dispute, he could command each side to produce Proofs. Put another way, the litigants were given a chance to prove their cases with supporting evidence. Another judge, the Lord Ordinary on Oaths and Witnesses, heard witness testimony in Edinburgh. If witnesses could not be deposed in the Scottish capital, he issued commissions granting authority to judicial officials in Scotland or abroad to perform the same task.

The Lord Ordinary on Concluded Causes packaged the legal arguments, accompanying witness testimony, and relevant Session Papers into a printed document called the State of the Process or State of the Cause for full court’s consideration.

Examining the action in Cunninghames v. Dougal (1776) allows us trace the production of Session Papers over the course of a particular case. In December 1772, tobacco merchant Alexander Cunninghame died. Cunningham was the managing partner of the firm Alexander Cunninghame and Company. His brother, William Cunninghame, was one of the so-called “Tobacco Lords” who maintained near monopolies over the tobacco trade with colonial Virginia and Maryland. Alexander’s company operated in the latter colony. He left behind two young daughters, in addition to several corporate partners.

Shortly after Alexander’s death, a dispute arose between the company’s surviving partners over the value of the firm’s remaining shares. Alexander’s young daughters and heirs, Barbara and Elizabeth, sought to liquidate their inherited shares at a favorable price. James Dougall, a partner in the firm, contested the Cunninghames’ assessed price and the logic behind their valuation. The action came before Lord Kames as Lord Ordinary in the Outer House before it moved into the Inner House.

In early 1775, legal counsel for the Cunninghames and Dougall filed Informations with the court. In laying out their specific claims, the advocates included a wealth of facts and evidence of great value to researchers. Petitions and Informations commonly included reprinted primary source material such as correspondence, corporate charters, ledger extracts, estate plans, maps, and even poetry. Advocates might also include evidence in an Appendix attached to the main document. For example, in Hugh Rose vs. Macleay’s Trustees (1837), a dispute over the estate of a man involved in the West India trade, both the pursuer and defender included appendices with a combined total of over 300 printed pages of letters and account book extracts.

In Cunninghames v. Dougal, the advocates submitted the Cunninghame Company’s partnership contract, a list of the shareholders and the number of shares each partner held, and correspondence between partners in Glasgow and their employees in Maryland. The letters are of particular interest. They detail the company’s struggle to deal with falling tobacco prices in the wake of the 1772 credit crisis that swept through Great Britain, and the loss of a company store in Maryland to fire. Taken together, the arguments and the evidence enable a preliminary reconstruction of the firm, the personal and professional relationships between the partners, and the company’s place within the transatlantic economy.

Document titles are rich in both biographical and geographical detail. Their formulaic design conveyed certain known facts about a litigant. For example, on February 8, 1775, William Craig filed an “Information for Elizabeth and Barbara Cunninghames, daughters and only children of the deceased Alexander Cunninghame, merchant in Glasgow, and their tutors; against James Dougal, merchant in Glasgow.” Without having read the document, we learn that both Elizabeth and Barbara were minor children and heirs of a deceased Glaswegian merchant. Their tutors, or trustees, brought the lawsuit on their behalf against James Dougal, also a merchant from Glasgow. The document itself served to inform the judges about the state of Elizabeth and Barbara’s claim.

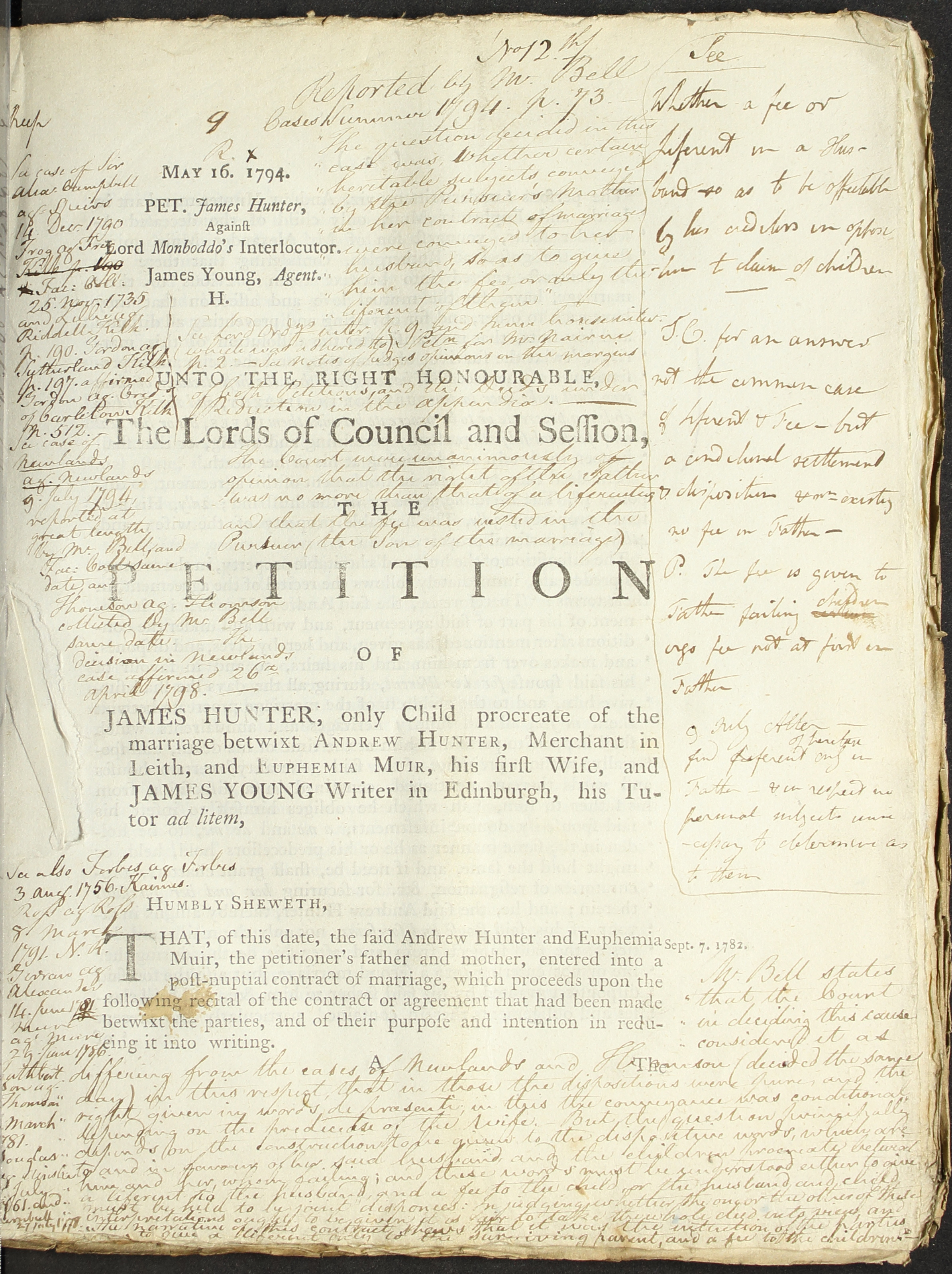

Craig’s participation in Findlay v. Graham (1773) is another example of how document titles provide critical details about a litigant. Like all Petitions filed with the court, the document’s title began with the phrase “Unto the Right Honourable the Lords of Council and Session.” The phrase, when paired with the main text’s opening line, “Humbly sheweth,” signaled the litigant’s supplication.

Craig, however, went a step further in Findlay v. Graham. In, “Unto the Right Honourable the Lords of Council and Session, the Petition of Poor James Findlay late Tenant in Keppoch, now in Glasgow, Pursuer,” Findlay is described as a “Poor,” benighted individual worthy of the court’s favor. The title indicates both his socio-economic status—he was a tenant on someone else’s land—and his movement through geographic space. We learn in the document that he was illiterate, thus contributing to the “Poor” appellation. It conveys Findlay’s humble submission before the court and his desire for pity.

In July 1775, the Lords of Session ruled in favor of the Cunninghame sisters. Dougal had submitted Additional Observations to augment his original Information, to which the sisters gave in Answers to his new claims. When the court ruled against him, Dougal almost immediately filed a Petition asking the judges to reconsider. Again, the sisters offered Answers, and again the court denied Dougal satisfaction. Dougal might have directly confronted these Answers with Replies, which might have in turn have triggered Duplies, Triplies, and more from both parties. He chose file a final Petition in March 1776, but to no avail.

By the time of Craig’s death in 1813 the format of Session Papers had begun to change. Parliament’s reforms in the preceding years and the court’s own initiatives altered Session Papers’ structure in the interest of more efficient justice. The papers that advocates submitted to the court in the 1820s had a familiar yet different form than documents produced fifty years earlier.

Take a moment to peruse the documents in Macindoe v. Cowley, Wallace, Crawford, and French (1780). This cause was about the forced impressment, and eventual desertion, of a Glaswegian hair-dresser into the British Army during the American Revolution. In the case documents we find that legal arguments, counter claims, facts in law, and evidence are sometimes mixed together without a clear delineation between the different sections. The exception is the Proof, which contains evidence.

You now have some sense of the arduous task the Lords of Session faced as they dealt with each case. It was not uncommon for the Lords to read through one thousand pages or more during the summer and winter terms. In 1789, for instance, litigation in the Inner House resulted in 24,930 quarto pages of printed material.

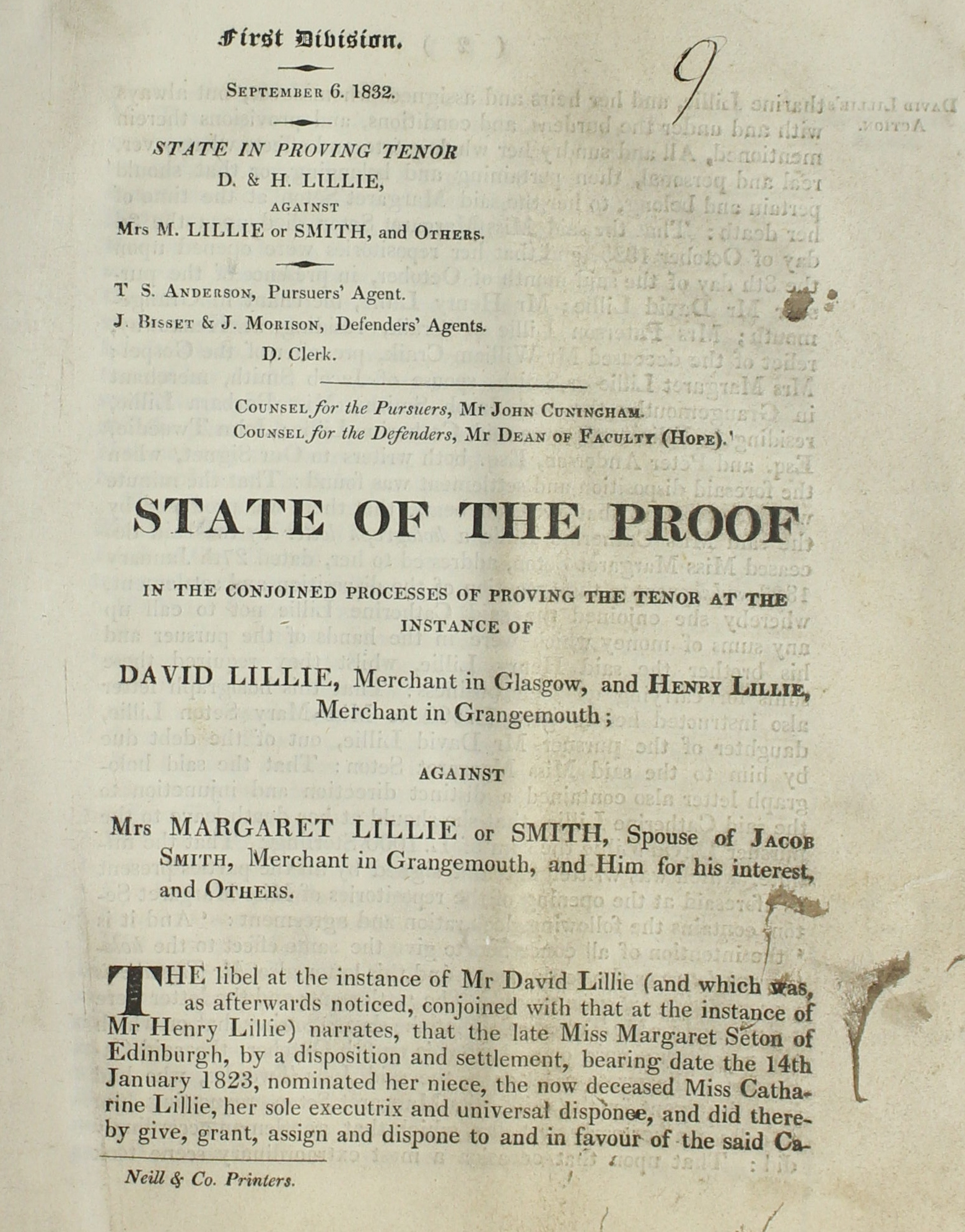

We can see the nineteenth-century’s structural reforms at work in the Session Papers for a case like David and Henry Lillie v. Mrs. Lillie or Smith, and Others (1832). This was a family dispute over an inheritance claim.

We can see the nineteenth-century’s structural reforms at work in the Session Papers for a case like David and Henry Lillie v. Mrs. Lillie or Smith, and Others (1832). This was a family dispute over an inheritance claim.

The revised format is readily apparent on the title page of the first document. Earlier Session Papers sometimes lacked a formal header; in later documents like this State of the Proof we often find elaborate headers structured for informational and organizational efficiency. The header informs us that the Inner House’s First Division heard this case, the date on which the document was submitted to the court, the case’s proper title, and the names of the agents and counsel for the pursuers and the defenders.

The title page an of earlier dated document, "Revised Condescendence and Note of Pleas in Law," conveys similar information.

The headers no doubt made it easier for the College of Justice to keep track of Session Papers as litigation moved through the court.

Headers introduced the reader to documents considerably more compartmentalized and demarcated than their eighteenth-century predecessors. The "Revised Answers, and Notes of Pleas in Law" in the Lillie case demonstrates this change. Advocate John Hope, the Lord President’s son, responded to his adversary’s submission with his own set of facts and legal claims. Like his counterpart, Hope offered the court a document separated into individual parts. In the first section, Hope confirmed or rebutted each of advocate John Cuninghame’s factual claims, using ordinal numbers and specific paragraphs to delimit each response. In section two, he presented his own client’s similarly ordered statement of facts. Hope offered his pleas in law in section three. He, like Cuninghame, arranged his pleas in an ordinal list to distinguish one point from another. In the final component, Hope included an appendix of supporting evidence, including excerpts from David Lillie’s ledger and correspondence between Lillie and his sister, Catherine.

The format of nineteenth-century Session Papers in cases like the Lille cause may have made their use by judges, lawyers, and aspiring legal professionals far more efficient. By presenting information in an ordered fashion, the revised structure likely made it easier for court officials to parse the legal arguments and evidence contained within while enabling readers to draw clearer connections between and across the documents in a particular case.

But how do we know how the court ruled in any given case? And in what ways did Session Papers inform what budding attorneys, practicing advocates, law professors, and even judges could know about the court’s previous decisions?

In the essay’s final section, we address the crucial role that collecting and curating Session Papers played in shaping legal—and thus historical—knowledge. The transition to print in the early eighteenth century meant that Edinburgh-based printers could produce multiple copies of Session Papers at scale. In the absence of advanced law reporting, the aggregation of Session Papers into personal and institutional collections became an essential way for the community of the College of Justice to read through past cases, grapple with the court’s previous decisions, and apply lessons learned in the future.

Collecting and Curating Session Papers

In the modern era, we are accustomed to reading a supreme court’s published written opinions. Scots lawyers in James Boswell’s or Sir Walter Scott’s time did not have that luxury. The Lords of Session delivered their decisions orally and they were under no obligation to explain the rationale behind their votes. A simple majority carried the day. On many occasions, a frustrated litigant would have been at a loss to explain why she or he lost a cause.

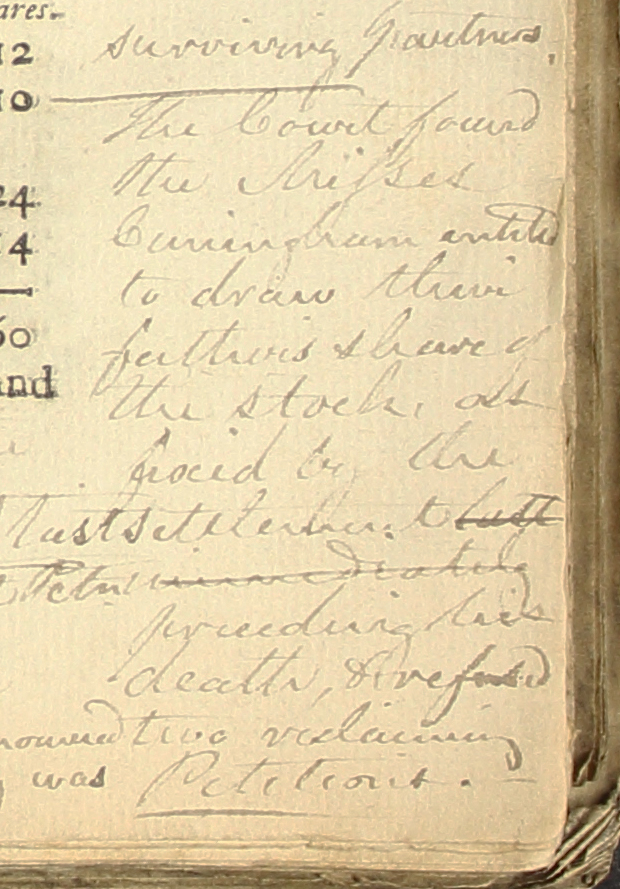

In Dougal’s legal battle with the Cunninghames, the court’s refusal of his final petition was written on the title page of the Information submitted by Craig on February 8, 1775. The handwriting is not Craig’s; it may be that of Andrew Skene, the Aberdeen-born advocate who may have later came into possession of Craig’s Session Papers, or more likely that of a clerk.

In Dougal’s legal battle with the Cunninghames, the court’s refusal of his final petition was written on the title page of the Information submitted by Craig on February 8, 1775. The handwriting is not Craig’s; it may be that of Andrew Skene, the Aberdeen-born advocate who may have later came into possession of Craig’s Session Papers, or more likely that of a clerk.

Duplicate copies of the same case held in Edinburgh libraries may contain marginalia from a different advocate or judge involved in the proceedings that may shed greater light on how they interpreted the legal arguments within. Or they may contain no marginalia at all. In other examples, advocates recorded a judge’s words as he spoke them in court. These cases give us a seat in the Inner House to “hear” the judges deliberate and issue their opinions from the bench.

Scots lawyers did not have access to robust sets of published Court of Session decisions either. Unlike their common law Anglo-American counterparts, who relied on law reports compiled by jurists such as Sir Edward Coke, Lord Chief Justice John Holt, or Sir Richard Hutton to study the foundation and evolution of English common law, Scots had comparatively fewer case reports at their disposal. Lord Kames and other editors did publish some volumes of “remarkable” cases earlier in the eighteenth century, but systematic efforts to compile and publish Session decisions did not begin until the 1760s and few comprehensive indices or digests existed before the early 1800s.

The relative dearth of law reports in Scotland until the late eighteenth century can be explained in part by the significance of the judicial precedent to common and civil law. In short, precedents mattered much more to eighteenth-century Anglo-American common law lawyers such as Thomas Jefferson and John Adams than they did to Scots advocates like William Craig or Adam Rolland of Gask . Precedents are a major source of law in common law countries. They are created by judges in earlier court decisions and they inform how future courts might or must rule in similar cases. In civil law societies, however, the legislative statute reigns supreme. The court is more concerned with how a statute applies to the case currently before it than it is with its past rulings on the same subject.

Lord Cooper of Culross, who served as Lord Advocate in the early twentieth century, framed the distinction between the two legal systems in terms of the questions that common and civil lawyers asked at the beginning of a new case. A common lawyer inquired, “What did we do last time?” A civil lawyer pondered, “What should we do this time?” The former seeks judicial remedies while the latter “thinks in terms of [the] rights and duties” expressed in the statutes.

As precedents were not as important to Scots advocates as they were to English barristers or American common lawyers, personal and institutional Session Papers collections were a key means by which the Scottish legal community learned the law and explored the court’s past decisions. Along with foundational texts such as James Dalrymple, 1st Viscount of Stair's Institutions of the Law of Scotland (1681) and John Erskine of Carnock's An Institute of the Law of Scotland (1773), Session Papers were a critical tool in the production of legal knowledge and learning.

Members of the College of Justice often assembled highly organized Session Papers collections during their lifetimes. While we know little about each individual’s curation strategies, surviving libraries make clear that personal holdings reflected one’s own legal career and cases deemed significant by the wider legal community.

William Craig, who owned many of the papers now held by the UVA Law Library, collected cases in which he was involved (first as an advocate and then as a judge) and prominent cases in which he had no role. Craig kept copies of documents that he authored as well as those produced by his opposing counsel. His handwritten marginal notations reveal his engagement with the legal and factual claims of his adversaries, the merits of a case before him as a judge, and commentary on other litigation. On some of the pages Craig captured the court’s decision. And like many other members of the community, he had his papers bound into volumes by a local Edinburgh binder.

Craig was by no means unique. Lord Kames, Sir Ilay Campbell, Robert Dundas of Arniston, and others jurists built similar collections. Many of their personal libraries now reside in the Faculty of Advocates Library or the Society of the Writers to the Signet Library in Edinburgh. In August 1769, James Boswell spent several evenings “sorting a large mass of session papers belonging to my father and selecting such as are worth binding.”

The Faculty of Advocates Library and the Society of Writers to the Signet Library built institutional Session Papers collections as well. In the early eighteenth century the Faculty created the office of “Collector of Decisions,” and charged one of their number with compiling the court’s opinions with an eye toward future publication.

By mid-century the work had become unmanageable for a single advocate. In 1751, the Faculty began appointing four volunteer collectors annually to scour the material. Their goal was to publish volumes containing the court’s decisions.

In 1760, the Faculty published Decisions of the Court of Session, from the beginning of February 1752, to the end of the year 1756. This first volume and later additions did not account for every case represented in the Advocates Library’s Session Papers.

The details of when the Signet Society Library began collecting Session Papers are less clear. While a surviving manuscript catalog from c.1763 provides evidence of significant holdings by that point, Society member Robert Bell’s published reports from the early 1790s suggest that the Signet Society had yet to adopt a formal collection plan. By the 1820s, however, collection efforts were assuredly underway. And like the Advocates Library, the Signet Society Library grew its holdings by purchasing private collections from their owners or at estate sales.

The act of organizing and marking up Session Papers imbued them with legal meaning and authority.

Marginalia reveals how a lawyer, judge, clerk, or librarian organized Session Papers to make them more conducive to legal research and learning. Curators typically bundled related case documents together within a bound volume. They assigned each bundle a number that often corresponded with a handwritten case index at the beginning of the volume. Signet Society Librarian Alexander Mill’s early twentieth-century herculean efforts to create a master record of the library’s collection reveal the indexing process.

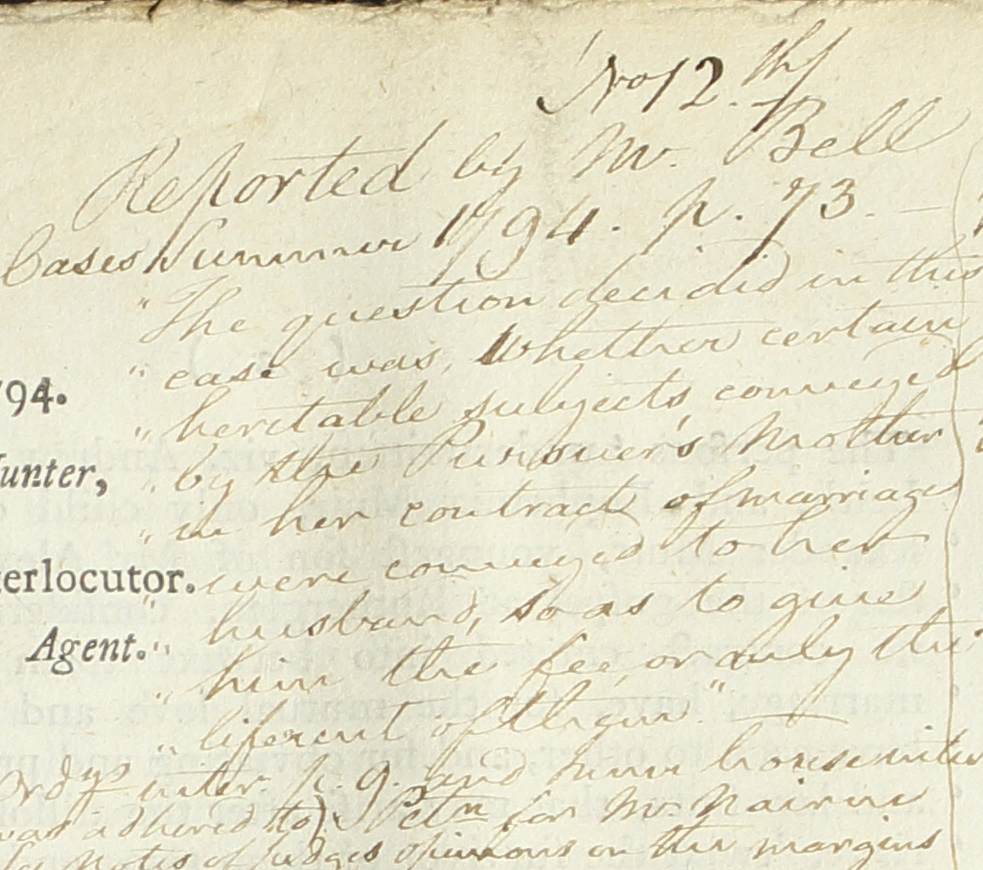

The materials in the UVA Law Library’s collection signal how their previous owners used marginalia to establish relationships between case documents and published texts like Decisions of the Court of Session or to similar, unreported, cases in another library. The lead petition in the cause of Hunter v. Hunter’s Creditors (1794) is an excellent example of this deliberate act of authority making. As we can see, the petition’s cover page is heavily annotated by at least two different people. The number inscribed at the top tells us that the petition and the documents that follow comprised the 12th bundle in the now disbound volume.

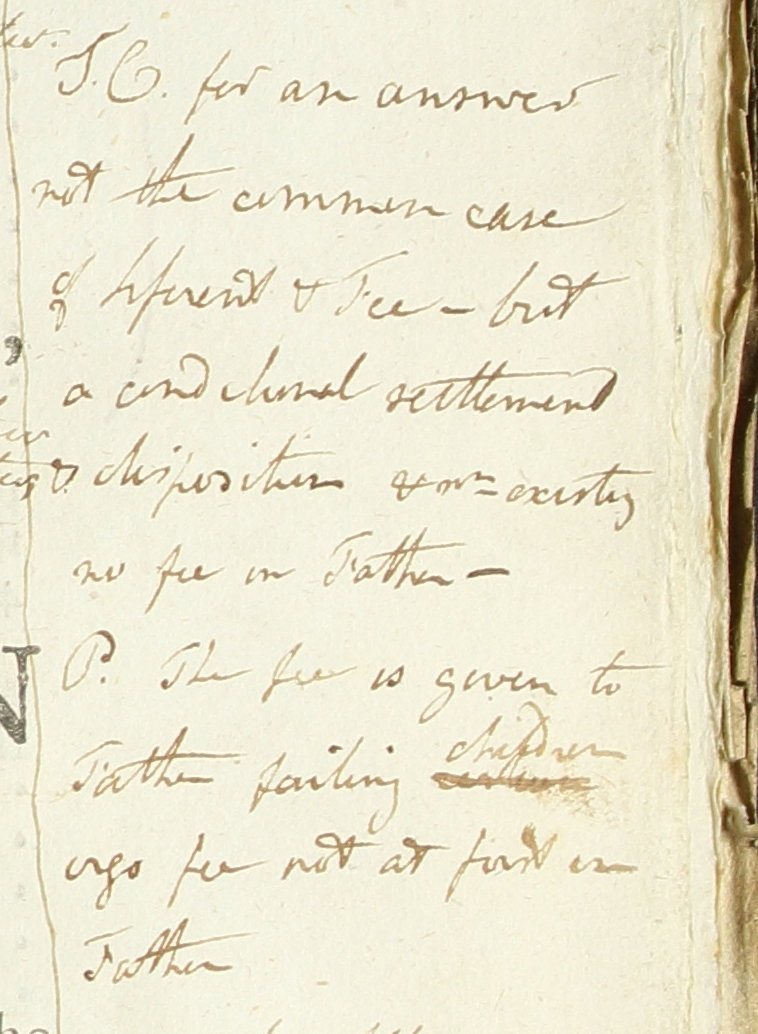

William Craig, by now a judge on the court, scribbled on the page’s right-hand side. He captured the Lord Justice Clerk’s and the Lord President’s opinions on the petition, using the initials “J.C.” and “P” to identify them.

At some later point another individual, likely an advocate, clerk, or librarian, sectioned off Craig’s notes by drawing a line around them before adding fresh marginalia to connect Hunter v. Hunter’s Creditors with reported and unreported cases. The notation at the top of the page reads, “Reported by Mr. Bell Cases Summer 1794. Pg. 73.” It is a reference to Robert Bell’s 1796 publication, Cases decided in the Court of Session, during summer session 1794, winter session 1794-5, and summer session 1795. The citation is followed by excerpts from Bell’s case report, with internal references to the case documents interspersed among them.

At some later point another individual, likely an advocate, clerk, or librarian, sectioned off Craig’s notes by drawing a line around them before adding fresh marginalia to connect Hunter v. Hunter’s Creditors with reported and unreported cases. The notation at the top of the page reads, “Reported by Mr. Bell Cases Summer 1794. Pg. 73.” It is a reference to Robert Bell’s 1796 publication, Cases decided in the Court of Session, during summer session 1794, winter session 1794-5, and summer session 1795. The citation is followed by excerpts from Bell’s case report, with internal references to the case documents interspersed among them.

The series of citations along the petition’s left side point to related litigation reported in Bell’s Cases, the Faculty of Advocates’ Decisions, and to unreported cases presumably found in another bound volume.

The series of citations along the petition’s left side point to related litigation reported in Bell’s Cases, the Faculty of Advocates’ Decisions, and to unreported cases presumably found in another bound volume.

By inscribing the petition with extensive citations and extracts, the curator incorporated the petition and its parent bundle into a larger constellation of legal knowledge comprised of Session Papers and published texts. The marginalia served as a kind of way finder for readers, helping them to navigate among a number of sources to identify and access relevant information. In the digital computing age, we might think of the petition as a node in a database and the marginalia as hyperlinks to external sources. Together, the marginalia, inscribed page, and document bundle enabled a lawyer to interrogate the specifics of a particular case and its place within the larger Scottish legal universe.

Conclusion

Session Papers tell the stories of British Atlantic peoples in an era of profound historical change. Advocates pleaded their clients' cause before the Lords of Session in Edinburgh, but the evidence they submitted and the papers they produced often had Atlantic implications. The papers in this collection, and those that reside in Edinburgh libraries, are windows into their lives and the events that shaped them.

By shining a light on these documents we can begin to recover histories that have been long hidden in the archives, histories that were once the subject of vigorous legal debate in the Court of Session. Inscribed with marginalia and packaged into bound volumes, Session Papers became sources of Scottish legal authority as well as very personal reflections of one's own legal career.

Much work lies ahead to recover the people, places, and controversies within these documents. So, too, does the challenge of documenting, digitizing, and describing Session Papers and cases in other libraries. SCOS provides one possible model for this collaborative endeavor. If, as the historian Finley notes, the College of Justice's purpose was to deliver justice to the king's subjects, SCOS strives to make their voices heard once more.