James Dunlop Jr. incurred substantial debts, in which his father, James Dunlop of Garnkirk, became jointly bound. In 1763, James Jr. became insolvent and transferred his effects to Alexander Spiers, and others, as trustees for his creditors. To protect James Sr., several friends, including Thomas Dunlop, purchased the debts for which James Sr. was jointly liable. To secure these debts, James Sr. granted the friends a bond over his estate; he subsequently conveyed the estate to them in trust, subject to certain provisions for his children. As a result, Thomas Dunlop et al. were creditors with respect to the joint debts, as well as trustees of James Sr.’s estate. In 1772, Spiers et al. advertised a dividend from James Jr.’s estate and invited creditors to submit their claims. Thomas Dunlop et al. submitted a claim but were refused; they then sued. Spiers et al. argued that the refusal was justified because James Sr.’s marriage contract promised the entire estate of Garnkirk to James Jr. Therefore, according to Spiers et al, Thomas Dunlop et al. should collect payment from the estate that they already controlled. Further, Spiers et al. argued that James Sr.’s trust disposition required the same result. However, Thomas Dunlop et al. argued that as creditors, they were entitled to attack James Dunlop Jr. for payment. On June 26, 1776 the Court determined the pursuers as creditors of Dunlop, junior were entitled to be ranked along with his other creditors. On July 31, 1778 they limited the amount the pursuers could draw upon Dunlop, junior's estate, however they reversed this ruling on November 28. The defenders then petitioned the Court to alter their last interlocutor. The issue of the marriage contract was eventually resolved in Alexander Spiers and Others v. Thomas Dunlop and Others.

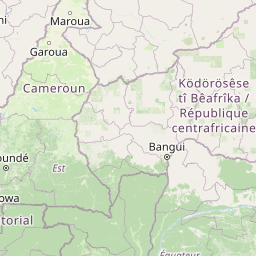

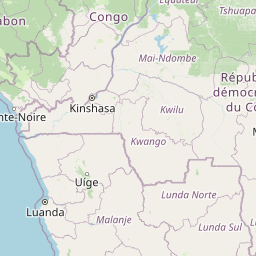

Locations